As of now, written and directed by DumplingThe film has already surpassed 300 million viewers and 14.5 billion at the box office. As the second instalment of the "Ne Zha" series, the film further introduces the grandiose worldview of "The Feudal Mysteries" and has attracted the attention of audiences around the globe with its stunning visual presentation, innovative and unique characterisation, and sweeping plot design. Particularly praiseworthy is the production team's craftsmanship in props and environmental details, which fully draws on the rich heritage of excellent traditional Chinese culture, creating a new level of localised animation creation.

In the previous film, Ne Zha: The Descent of Nezha, a large number of Chinese cultural relics have been incorporated into the film. For example, when Nezha was born, Taiyi Zhenzhen drank wine in a swirling coloured pottery pot similar to that of the Majiayao culture, and at Nezha's third birthday party, goblets and cymbals (musical instruments) from the Shang and Zhou dynasties appeared in the scene of the orchestra's performance, which is very similar to that of the Tang Three-colour Camel Carrier Figurine. In "Ne Zha's Magic Child Troubles the Sea", traditional Chinese elements are subtly infiltrated into every detail, giving the film a strong oriental aesthetic flavour.

The seven colours of the Baolian are derived from the Boshan Furnace.

Seven-coloured Pauline Photo credit: People's Daily

Western Han Dynasty gilt-bronze Boshan burner, belly diameter 15.5cm, height 26cm, Hebei Provincial Museum, photo credit: Hebei Provincial Museum

The seven-coloured Baolian is one of the most important magical treasures in the film, capable of helping Ne Zha and Ao Bian to remake their physical bodies, and is inspired by the Boshan Stove. The Boshan Furnace is a common incense burner in the Han and Jin dynasties, made of bronze and ceramic. The body of the furnace is in the shape of a bean of bronze, with a high and pointed hollowed-out mountain-shaped lid, and when the incense burner is ignited, the mountain will be covered with smoke, just like the "Boshan", the immortal mountain at sea, and the name of the furnace comes from this. Is derived from this, this artifact has been a unique shape by the royal family to the folk widely loved. In addition, the seven-coloured lotus petals are also painted with cloud patterns, adding a sense of magnificence.

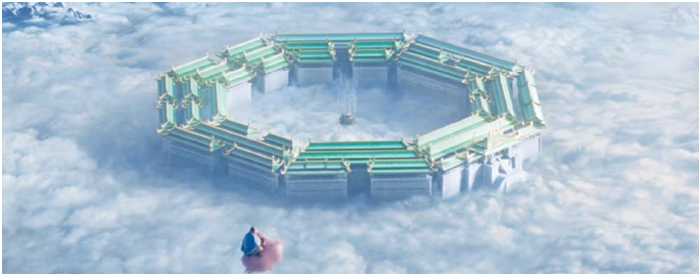

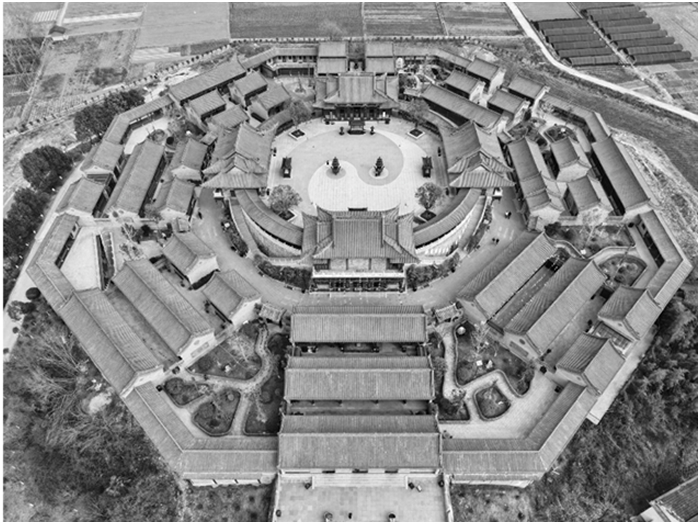

The template for the Jade Palace is the Hanzhong Heavenly Master's Hall

Jade Hollow Palace Photo credit: Official microblog of the film Ne Zha's Magic Child Haunts the Sea

Jade Hollow Palace Photo credit: Official microblog of the film Ne Zha's Magic Child Haunts the Sea

Tianshidang Source: shaanxi.com

Located in the Kunlun Mountains, the Yuxu Palace is an octagonal courtyard complex consisting of multiple monoliths, evolved from the Nine Palaces and Eight Formations, and is similar in architectural style to the Tianshidang Hall in Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province. Tianshidang is a Taoist shrine, first built by Zhang Lu, King of Hanzhong during the Eastern Han Dynasty, which visually represents the Taoist philosophy of the Eight Trigrams.

Yuxu Palace is a reference to the Han Dynasty high-topped pavilion-style architecture, with a green glazed tile roof, a ridge brake in the form of a sacred bird, scops owls on both sides, plaques under the eaves, and cloud patterns on the pedestal, which blends the styles of traditional wooden buildings from various eras.

Palace Birds Pay Tribute to Song Huizong's "Ruihe

Exterior view of the Jade Palace Photo credit: CCTV News

(Northern Song Dynasty) Zhao Ji, "Ruihe" (part), colour on silk, in the collection of the Liaoning Provincial Museum

When the Jade Palace first appeared, there was a flock of birds flying above the blue sky on top of the palace covered with green glazed tiles, a scene that pays homage to the Song Emperor Huizong's "Ruihe Picture", now in the Liaoning Provincial Museum, which depicts the Xuande Gate in the compilation year surrounded by colourful clouds, with a flock of cranes circling on top of it, and two cranes residing on top of the scops' tails. The inscription of Song Huizong on the left side of the picture explains its content. On the second eve of the first year of the second year of the Northern Song Dynasty (i.e., 16 January 1112), auspicious clouds suddenly appeared in the sky over Bianjing, and two cranes landed on the scops owl of Xuande Gate, which was regarded as an omen of good fortune and was recorded. Although this work may have been recorded as an auspicious event fabricated for the purpose of consolidating the rule, the composition of this work, with the combination of flowers, birds, and landscapes, showing a large area of the sky and the roof, and the extremely brilliant stone-blue sky, was loved by viewers of all ages and has been passed down since then.

Jade Hollow Palace Photo credit: Official microblog of the film Ne Zha's Magic Child Haunts the Sea

The staircase and the square lotus pond of the Jade Hollow Pavilion were borrowed from the "Fish Swamp Flying Beam" of the Jin Ancestral Temple in Shanxi Province. The "Fish Marsh Flying Beam" is the earliest land and water bridge in China, built before the Northern Wei Dynasty, and is basically in the form of the Song Dynasty. Yu Numa, meaning round pool, flying beam refers to the cross-shaped bridge on the marsh, "Yu Numa flying beam" including stone pillars, arches, wooden beams, railings, watch posts, iron lions and other parts. In the film, all the buildings are made of jade to create a white and sacred atmosphere of the Jade Palace.

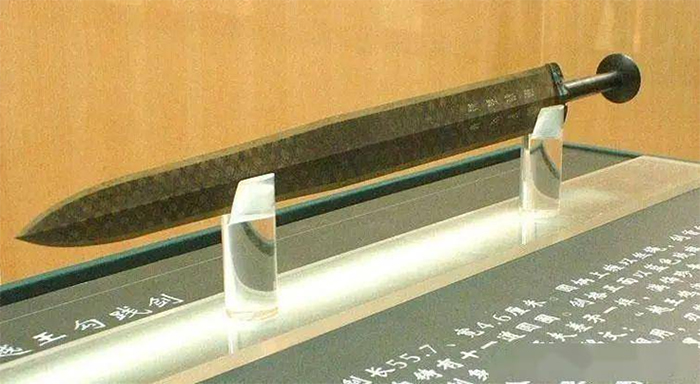

The prototype of Lady Yin's bronze sword is the Yue Wang Goujian Sword.

Lady Yin's Sword

Buddhist monk's sword (archaic)

A large number of bronze weapons are featured in Ne Zha's Magic Children Haunting the Sea. Mrs Yin uses a typical Warring States bronze sword with a rounded head and double hoops, which is represented by the Yue Wang Goujian Sword. The body of the sword has a diamond-shaped pattern, and the hilt is wrapped with purple silk Gou, which is favourable for gripping.

Ao Guang Poster Photo credit: Guangming.com

Jade knife, Shang, bronze, Yinxu Museum Collection Photo credit: The Economic Observer

Dragon tooth knife used by Aoguang, the Dragon King of the East China Sea, the first half of the reference to the bronze knives of the Shang Dynasty, such as the bronze knives of the Xinguan Dayangzhou Tomb in the collection of the Jiangxi Provincial Museum, and the Shang jade knife in the collection of the Yinxu Museum, the tip of the knife is upturned, the knife's belly is closed to the arc, the back of the knife has a tooth decoration, and the dragon swallowing mouth at the bottom of the swallowing mouth of the knife's blade is a symbol of the high-level Guanjiao knife, which was prevalent from the Tang Dynasty to the Ming Dynasty, and it can be seen thatYu Ming "Guan Yu Capturing Generals" The design of this sword is a mixture of styles from different eras and regions.

Three-Go Bronze Halberd, Warring States - Zeng, Bronze, Collection of the National Museum of China Photo credit: National Museum of China

The weapon of the soldiers at Chentangguan is a halberd from the Warring States period, which is basically the same as the bronze halberd of the Warring States period in the collection of the National Museum of China, with a spear in the front for intercepting and a go in the lower part for hooking and killing.

Li Jing Image Source: Film Ne Zha's Magic Boys Haunting the Sea Official Weibo

Patterns of bronze were also applied. The motifs on the bronze armour and body armour of Lady Yin and Li Jing draw on those used in bronze, and the hooked arc of the breastplate draws on the brow of the animal face of the bronze tripod, achieving a refreshing transformation of traditional motifs between different media.

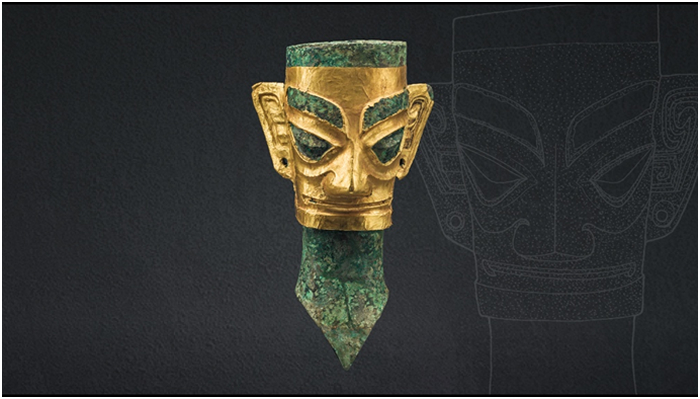

The "Boundary Beast" is a shape derived from the Sanxingdui culture.

Knotty Beast Image Source: Film Ne Zha's Magic Boy Haunts the Sea Official Microblog

The styling of the two important supporting characters, the thick-browed "Jiejie Beast" and the curled-nosed "Jiejie Beast", are closely related to the Sanxingdui culture. The thick-browed "Jiejie Beast" has thick eyebrows and an exaggerated garlic nose. The thick-browed "Junction Beast" has thick eyebrows and an exaggerated garlic nose, which is inspired by the bronze human head wearing a gold mask and the bronze animal mask, while the curled nose of the "Junction Beast" is very similar to the mouth of the bronze eagle-shaped bell.

Bronze figure wearing a gold mask, Shang Dynasty, Bronze, Collection of Sanxingdui Museum, Collection of Sanxingdui Museum Photo credit: Sanxingdui Museum

Bronze Beast Mask, Shang Dynasty, Bronze, Collection of Sanxingdui Museum Photo credit: Sanxingdui Museum

Sanxingdui Culture, located in Sanxingdui Town, Guanghan City, Sichuan Province, is a site of Shu culture from the Neolithic Age to the Shang Dynasty, in which thousands of precious artefacts have been unearthed, mainly bronze and gold ornaments, containing human figures, human masks, sacred trees, suns, animals and birds, etc., which are characterised by the co-existence of kingship and divine power. The face of the Sanxingdui culture is very different from that of the Shang culture of the Central Plains and is more difficult to understand, but it is also loved by contemporary people because of its mysterious nature. The reference to Sanxingdui culture in Na Zha's The Descent of the Demon Child satisfies the audience's needs in this regard.

The "Tianyuan Ding" borrowed from the flat-footed tripod, the bronze dun

Tian Yuan Ding in the animation

Flat-footed tripod with dragon motif, Late Shang Dynasty, bronze, Shanghai Museum Collection Image source: Shanghai Museum

Bronze dun, middle to late Warring States period, Hubei Provincial Museum Photo credit: Hubei Provincial Museum

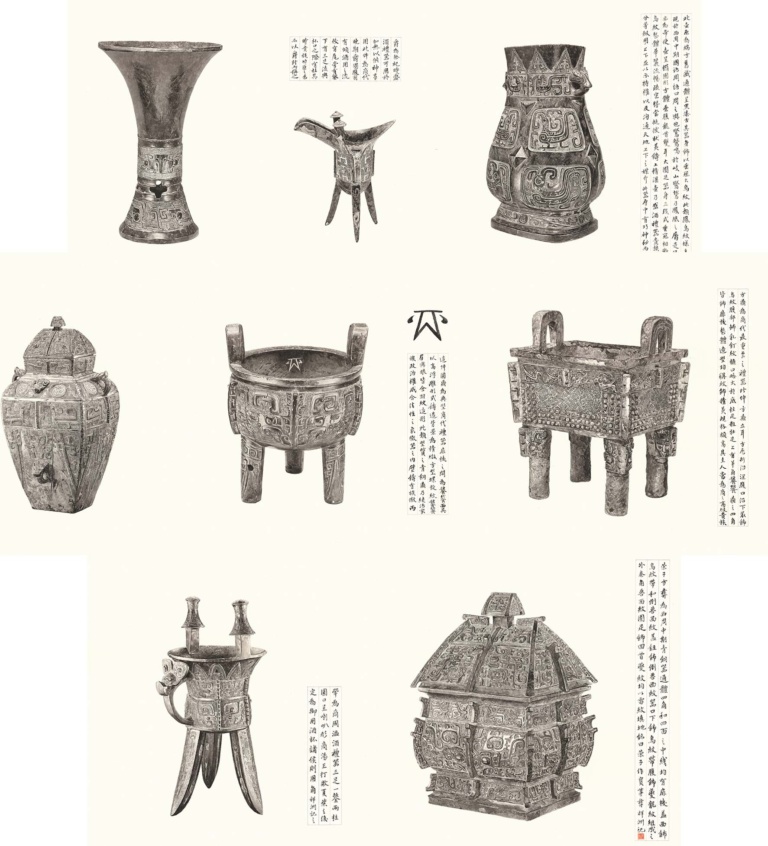

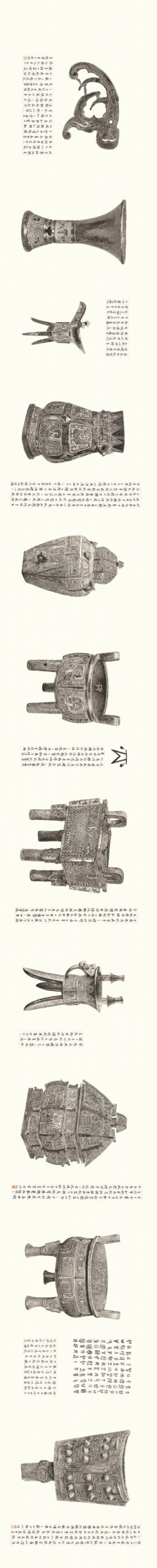

One of the most used traditional elements in Na Zha's The Magic Boy Who Troubles the Sea is the use of bronzes. The "Heavenly Yuan Ding", the main treasure of the Jade Palace, is divided into two parts, the large and the small, each of which references a different type of bronze vessel.

Bronze, an alloy of red copper and tin, was first produced in the Xia Dynasty and reached its peak in the Shang Dynasty, using the hot casting method. Although it lost its original ceremonial value after the Qin Dynasty, bronze is still regarded as a representative of Chinese culture with its unique charm.

The small tripod draws on the abdomen and feet of the flat-footed tripod with dragon motifs in the Shanghai Museum, while the rounded shape of the large tripod draws on the bronze dun in the Hubei Provincial Museum, on which the taotie motif is used. The dun was an eating vessel used to hold crops such as millet, grain, rice, and beams during rituals and banquets, and was prevalent from the late Spring and Autumn period to the late Warring States period, when it evolved from a storage vessel to a ceremonial vessel.

The groundhogs use a bronze kettle to cook their food.

Han string-patterned two-eared copper kettle, bronze, Collection of Hainan Provincial Museum

in the filmThe groundhogs used bronze kettles for cooking. The kettle is an eating vessel, a cooking utensil, which appeared in the middle of the Neolithic period, and became the main cooking utensil in the Three Kingdoms period, especially used in wartime armies, and the bronze kettle appeared in the Shang Dynasty.

In addition, the lower armour piece of Li Jing's cape is double threaded, referring to the cape of the armoured warrior in the mural painting of the tomb of Princess Changle in the Tang Dynasty; the dragon's head on the war armour of Ao Guang refers to the armour of the Heavenly King in the Tang Dynasty; the water hammer of Ao C is a weapon of the Song Dynasty, the Liao Dynasty, and the Jin Dynasty; the Lotus Terrace of the Taiyi Man is derived from the base of the copper-gilt and inlaid bead Buddha in the reign of the Qing Dynasty, and even the flames on the trousers of Na Zha, the lotus pattern of the blouse, the cloud pattern and water pattern on the dress of Ao C are all references to traditional Chinese motifs. Even the flame pattern on Ne Zha's trousers, the lotus pattern on his jacket, and the cloud and water patterns on Ao B's clothes are all references to traditional Chinese patterns. ...... The list of elements is endless.

To sum up, "The Descent of Nezha the Magic Boy" is not only an entertaining animated film, it is also a work that deeply integrates traditional Chinese cultural elements with modern art forms. Through the clever use of traditional Chinese cultural relics such as bronzes, architecture, ornaments, cultural symbols and other elements, the film brings the audience a visual feast in which tradition and modernity are blended, and solemnity and relaxation coexist. The re-creation of traditional elements in the film not only demonstrates the depth of the history of the Chinese civilisation, but also provides the audience with an opportunity to revisit and re-understand the traditional culture from a modern point of view.